Among marine organisms, jellyfish are certainly not our species’ favorites. Seeing them nearby while swimming triggers a sudden but justified sense of revulsion, given the stinging cells they possess, which are often truly dangerous even to humans.

Photo by LucViatour – Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

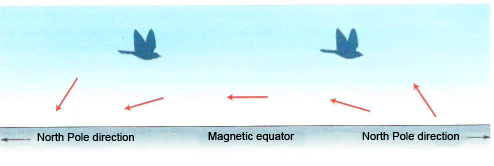

However, if we could for a moment ignore the unpleasant consequences of encountering them, we must acknowledge their elegance and beauty. Ethereal, transparent creatures, in soft pastel colors, they pulse rhythmically in the open seas, obedient to ocean currents and tidal movements, letting their long, tentacled arms dangle in the water column. Small, sometimes very small, but also large, very large, like the Arctic Coronatae, whose disc easily exceeds two meters in diameter.

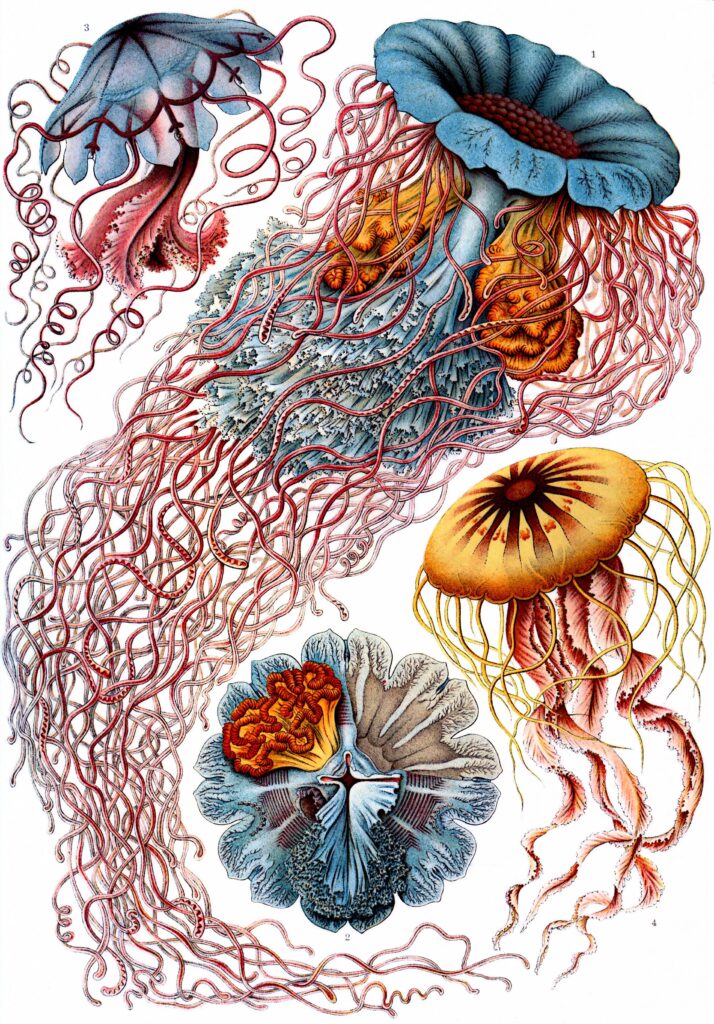

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Nineteenth-century zoological iconography has left us with stunning, almost unbelievable images of jellyfish in their colors and shapes, reminding us of their extraordinary biodiversity. The structure of the many jellyfish species always consists of a body shaped like a hemispherical dome from which hang numerous tentacles of varying sizes and shapes. At the center of the lower surface of the dome, a tubular manubrium supports the mouth, which leads into a large central cavity that functions as both a stomach and an absorbent intestine. Since an anus had not yet evolved at this stage, the cavity is blind.

The Velella velella, which belong to the related Hydrozoans, and the Portuguese Man-of-War, which actually belong to the Siphonophoran group, are not true jellyfish, even though they are often mistakenly considered as such.

photo by Wilson44691, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Rebecca R. Helm. Image by Denis Riek., CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

From an ecological perspective, jellyfish are characterized by a large number of species and remarkable biomass, constituting a significant percentage of the biomass of organisms populating the open waters of seas and oceans. Consequently, their presence in food webs is important, both as consumers and as prey. For example, sea turtles, which are among the most endangered species in the oceans, particularly favor them.

Their reproductive system can give rise to veritable “blooms” of individuals in response to various factors, both climatic and resource imbalances, thus constituting “sentinel” species useful for providing information on the health of the seas in which they occur. Indeed, such blooms are always linked either to excessively high sea temperatures, which are outside the expected range, or to abnormal concentrations of nutrients resulting from waters with high levels of organic pollutants.

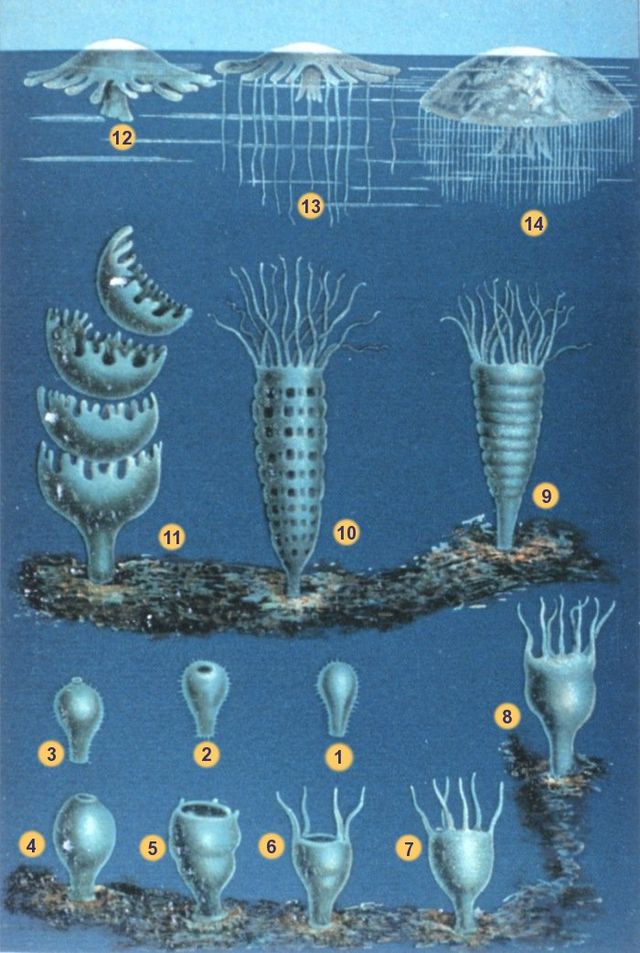

The diagram shows how free-living jellyfish have an initial larval polyp stage attached to the substrate, so that from a single initial larva, numerous series of adult medusae arise.

Image by Matthias Jacob Schleiden, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Of particular importance is their role in energy transfer within marine food webs. As consumers of minute plankton organisms, and even small fish, they accumulate the energy they represent, making it available to higher-order consumers, such as the vertebrates that prey on them. It should also be noted that these consumers are immune to the stinging and poisonous substances that are so effective against us!

On the zoological scale of structural evolution, jellyfish occupy very low levels, as part of the Coelenterates or Cnidaria, the group that includes red coral (which we use for jewelry), hydrozoans such as small Velellae, and reef-building corals with single species (anemones) and colonial species (gorgonians).

The jellyfish Chrysaora melanaster (Brandt, 1835); 2. The gorgonian Annella mollis (Nutting, 1910); 3. The coral Acropora cervicornis (Lamarck, 1816); 4. The anemone Nemanthus annamensis (Carlgren, 1943).

Image by Frédéric Ducarme, CC BY-SA 4.0 – via Wikimedia Commons

Jellyfish are among the most important invertebrate groups in marine and freshwater environments. Unlike their relatives, which often grow firmly on rocks, jellyfish are free-living individuals with adult lives in constant motion. To adapt to these conditions, they have evolved a “neural network” nervous system, with nerve cells not organized into a central brain structure, but rather into a network that pervades the entire body and is in contact with highly evolved and specialized sense organs, such as the eye spots, olfactory cells, and gravitational-sensitive sense organs that allow them to maintain a nearly vertical position. Although, as mentioned, at the mercy of currents, their dome-shaped bodies undergo continuous rhythmic contractions that, by narrowing and widening their diameter, generate a buoyant current that generates their autonomous movement.

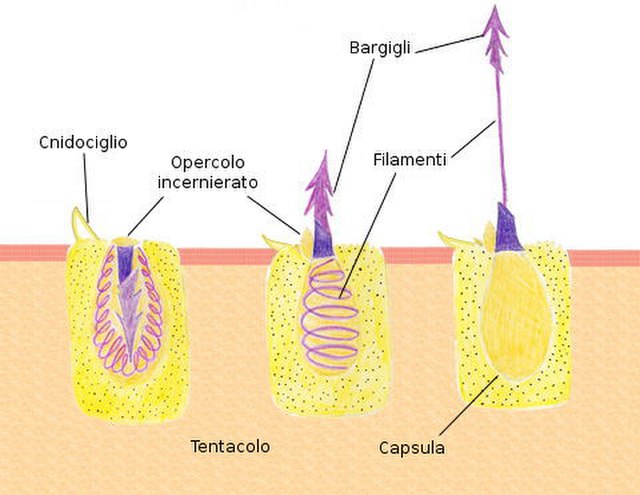

Of particular note are their stinging cells (nematocysts), a unique specialization of their group, which allows them to paralyze small organisms that come into contact with their tentacles, thus becoming their prey. These are extremely complex cells, equipped with a cilium that, when mechanically stimulated, causes the release of a tentacle often armed with spicules that help deliver the stinging liquid to the prey.

Mechanism of action of a nematocyst – Pubblic domain

Photo by Hans Hillewaert Creative Commons Attribution – Share Alike 4.0

We are certainly not their prey, but if we accidentally bump into them, we trigger a reaction that is not defensive, but merely a mechanical, reactive response from their hunting system.

The sea is their environment: to survive, they had to develop sophisticated predatory responses that could not be specific or guided by their array of sense organs, given the still primitive level of their structural design. Their world is without physical constraints, three-dimensional and boundless, as only the great oceans can be. They are not interested in us, while we can enjoy their beauty when we enter their habitat. However, let’s remember that they neither see us nor can they avoid us…

Credits

Author: N. Emilio Baldaccini Former Professor of Ethology and Conservation of Zoocenotic Resources at the University of Pisa. He has published over 300 scientific papers in national and international journals. Actively engaged in scientific education, he is also a co-author of academic textbooks on Ethology, General and Systematic Zoology, and Comparative Anatomy.

Translated by Maria Antonietta Sessa