It happens to those who love to wander along the shores of the Mediterranean, to always feel a bit ‘at home. It does not matter if you do not speak the same language, you can communicate easily when the gestures are the same, the same facial expressions with the same light-hearted smiles. But the feeling that ports have only different names is given by finding at each port identical lines in the architecture of fishermen’s villages or the same animal shapes carved in the gargoyles of the noble houses, but above all the same objects in each house.

At sunset, when the sun has just come down and the light has not yet decided to leave space in the dark, in all the small ports of the islands where the coasts are fragmented, or in the large ports that still host goitre and small fishing boats, we see the fishermen who with the same slow and careful gestures prepare nets and pots, all the same in function and in the invoice, change only a little the forms. It is the Mediterranean, the small great sea that feeds its people through objects built with infinite patience, weaving fibers and flexible branches.

Creation of a rattan fish trap

Creation of a rattan fish trap

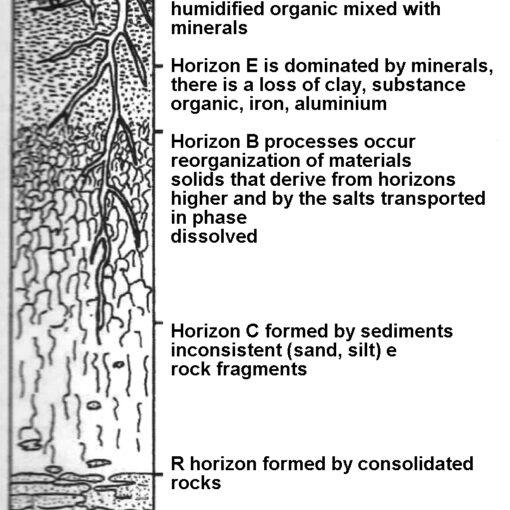

So the reeds (Juncus sp.), Finely intertwined and strung, become dead end holes for crabs, lobsters, octopuses and fish. The different shapes that the fishermen give to the traps do not change their function, but rather serve to better adapt them to the local seabed. The techniques of processing the rush or marsh grass that are used are, however, almost identical in almost all the Mediterranean coasts.

The bas-reliefs of the most ancient pyramids show vessels built with papyrus beams (Cyperus papyrus) bound together, with raised bow and stern and the almost flat bottom, which allows them not to hit the sandbanks that are found at a shallow depth, and drive through the numerous marshes without damage. The fishermen of Cabras, in Sardinia, until a few decades ago, for fishing in the lagoon and in the adjacent ponds, used little hollow boats (Cladium mariscus), with the raised bow and the flat bottom, is fassonis, which allowed them to navigate without problems even on almost surfacing seabeds. For identical needs, identical solutions were used, both in form and in the use of the raw material. Although herbs belong to different species, they have a similar feature that makes them suitable for the same purpose: they are plants adapted to water and even after cutting and processing maintain their ability not to rot.

So, in many Mediterranean countries the marsh grasses growing in the retrodunal wetlands have been used by the families of the fishermen also to make the roofs of their simple houses impervious to rain. Even the techniques with which these roofs are built, still observable in some cabras in Cabras, are very similar to each other.

Wetlands, both marsh and ditch, are very open, therefore extremely ventilated; it is also necessary that the trees that are part of this habitat make their supporting structures flexible. For this particular feature willows (Salix sp.) And tamarisks (Tamarix gallica), like most of the shrub flora of the bush, are extremely suitable to supply material to the weaving of the weaving.

To be used in the manufacture of chairs and baskets willows are pruned in such a way (cuttings) that in spring can produce a large number of jets suitable to be processed more easily. In Tuscany, next to the ditches that run along the vegetable gardens, there are always at least two or three willows showing clear signs of this type of pruning. The writer has found willows, of different species, but pruned identically, as well as in various regions of Italy, even in Yugoslavia, Greece and Spain.

The diffusion of objects, especially baskets, built with young branches of willows, tamarisks, filaments, vines, olive trees, or with reeds, straws and marsh grasses, is due above all to two reasons: economy and practicality.

The materials are available everywhere at no cost and in the family, at least until a couple of decades ago, there was always someone able to teach the art of weaving. It is not difficult for those who frequent peasant families to find a grandfather or a grandmother who can explain when it is time to cut young branches, if they have to be kept in a bath and for how long, and finally how to get a nice sturdy basket from that set of stems. The color of the freshly made baskets depended on the used twigs that could be dried and give a light color, or fresh and therefore greenish or purple. The only problem, for those who are not used to manual work, is to handle reeds and grasses without getting injured, but for this a couple of old gloves are enough.

The robustness and lightness typical of the baskets make these objects the ideal containers, so much so that they are defined in some regions of the south, with a dialectal term that underlines the easy use, the “comfortable”. Always used for harvesting fruit, wandering through the markets and campaigns of the Mediterranean belt, you can easily see how the shapes are varied and typical of each place. If you are curious about the precise use of each one, you will discover how each particular shape is well suited to the type of fruit it must contain: very open baskets for “delicate” fruit such as grapes and figs, narrow and tall for fruit that it is better to bear to be heaped like citrus fruits or apples, and so on. Also the way in which the branches of the trees from which the fruit has to be picked are arranged dictates the shape of the containers: therefore the baskets also adapt to the type of pruning in use locally.

Much of the cultivation of the Mediterranean area has been obtained from terraced hills, where the embankments are connected by narrow steep passages. The only help to the farmers is still given by donkeys and mules carrying tools and collected in baskets attached to the pack.

But it is not only farmers who use the art of weaving, breeders make cheeses using rush dumplings. Also in this case each locality has “its” cheese that takes the shape from its specific container.

In order to facilitate the escape of the oil from the paste of the ground olives, already in pre-Roman times and until a few decades ago, “fiscoli” were used, particular baskets that could be composed of different fibers (coconut, hemp, rush) and assembled in cords then twisted so as to form a double filter disc sealed at the edges and drilled in the middle. The olive paste was placed inside the fiscoli that were then stacked and covered by a pressing disc to cause the oil to come out of the pasta.

The weavings with which baskets, fuscelle, fiscoli, chairs, basti, pots, boats, were made represent only one of the cultural forms that express the close link between popular life and Mediterranean vegetation.

Those who love to reflect on the roots of their everyday life, questioning these simple objects listen to stories that do not relate to official history, made of wars that destroy, but a thousand stories composed of small daily gestures repeated endless times, capable of building great monuments to intelligence and laboriousness of women and men who knew exactly how many times they had to do the same laborious gestures for every slice of bread, every fish, every drop of oil and every piece of cheese that they placed with pride on their table.

Credits:

Author: Anna Lacci is a scientific popularizer and expert in environmental education and sustainability and in territory teaching. She is the author of documentaries and naturalistic books, notebooks and interdisciplinary teaching aids and multimedia information materials.

Translation by Maria Antonietta Sessa