“He popped up like a mushroom”; “You won’t tell me you didn’t see it yesterday, it’s not a mushroom!”

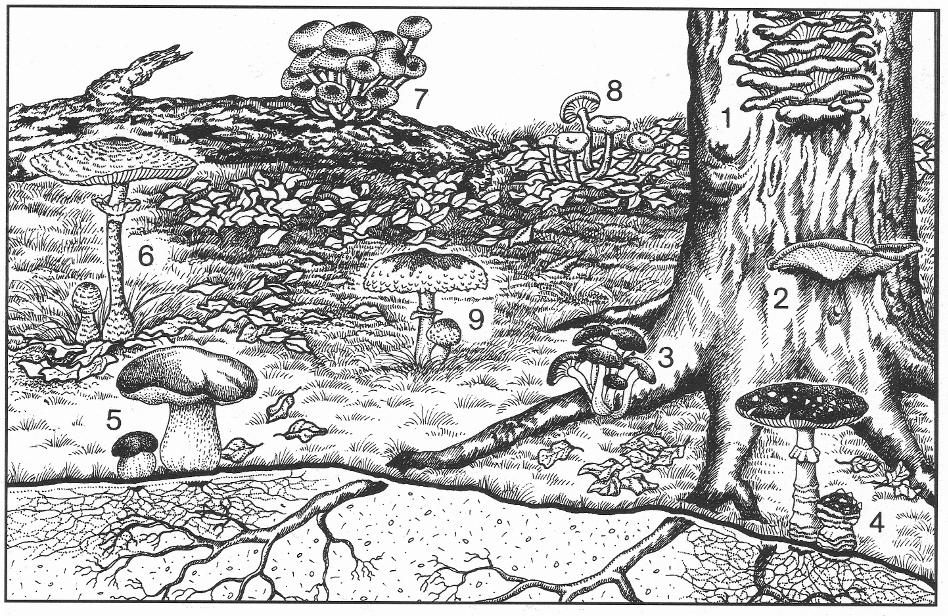

This is what happens, a few days after the rain: in the woods, as if by magic, we see them popping up almost everywhere, with their multicolored hats, their thousand shapes. A fruit is expected from a tree that has been there for years; a grass that sprouted a few days ago does not surprise us if it gives us a flower. So is it really the work of the elves when we see so many of them appear and so suddenly?

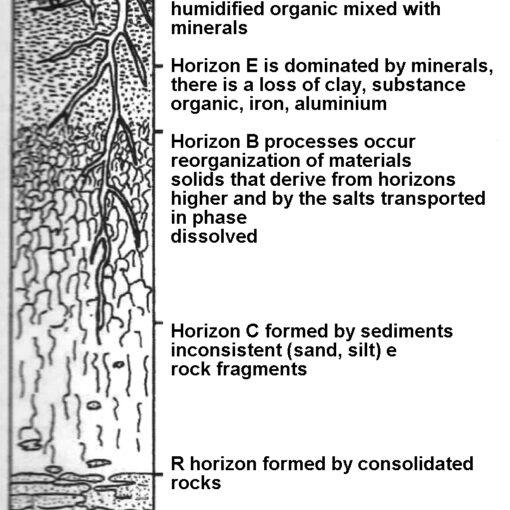

If you move away from the first layer of the litter, the more mobile and light one, we find a kind of white mold: it is the mycelium of mushrooms. Only when greatly enlarged we will see it as formed by thin filaments, the hyphae. It is an invisible net that runs under the litter and that manifests itself only when the fruiting bodies, which we call mushrooms, sprout. If we consider the large number of fruiting bodies that, depending on the time of year and the type of substrate we can find in the woods and we think that for each of them these invisible “threads” run in the ground, we will realize that, in addition to the woods we see, there is another tangled forest under our feet.

All mushrooms, if left to dry, release a kind of “powder”: the spores. When these reach maturity they fall on the ground, germinate and give rise to the hyphae, which in turn by elongating, branching and reuniting, form that more or less dense intertwining which is the mycelium or vegetative body, which will then give rise to new fruiting bodies, and so on.

If the hyphae, penetrating into the substratum from which they draw food, develop the fruiting body outside the surface of the soil, the fungus is defined as terricolous; if it grows directly on the wood of trees, stumps or roots, lignicolous; if like the truffle it grows underground, hypogeum.

Mushrooms lack the process of chlorophyll photosynthesis. They, therefore, need to feed directly on organic compounds, which are found both in the soil in the form of decomposing material and in plants or living organisms; they are therefore part of those organisms called heterotrophs.

The organic compounds that mushrooms need can be absorbed basically in three ways. In the event that they derive their food from decaying substances, both vegetable and animal, the fungi are called saprophytes. In the event that they invade another living organism, plant, or animal, and feed on causing damage or even causing its death, they are parasites; many parasitic fungi, after the death of the organisms that host them, behave as saprophytes. Then there is a last category of fungi: symbionts, also called mycorrhizal, which live in close contact with woody plants such as oaks, larches, firs, pines, birches, etc. They establish an exchange of nutrients with the host, at the level of the roots, with a consequent reciprocal advantage: the fungus wraps the extremity of the root hairs with the mycelium and removes sugar and starch from the plant; the plant in exchange receives water and mineral salts.

When we walk through the woods, therefore, we should avoid damaging the mycelium that runs under our feet; kicking a mushroom or picking it up by tearing it, can mean causing unjustified damage to those parts of the ecosystem that we cannot see.

Credits

Author: Anna Lacci is a scientific popularizer and expert in environmental education and sustainability and in territory teaching. She is the author of documentaries and naturalistic books, notebooks and interdisciplinary teaching aids, and multimedia information materials.

Translation by Maria Antonietta Sessa