The Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) is a small, plump, finely striped brown bird, with a proud and impertinent appearance that does not reach 10 centimeters in length. The short tail is constantly held up, helping to give it a vague brawler-like air. If its song is decidedly strong and melodious, with musical notes and persistent high notes, when alarmed it can turn into a harsh sequence from which the onomatopoeic Italian name (scricciolo) of the wren originated, with which it is officially known in Italy. The eighteenth-century zoologist Jean Luis Buffon rightly compares it (beak apart) to a “becasse en mignature” a small woodcock, and in Romagna it is called “coccla” or walnut since its thickness, roundness and color is similar to this one.

Very lively, it constantly moves in the foliage of the undergrowth in search of insects, larvae, and spiders perfectly at ease in the Mediterranean underwood as well as in the deciduous woods of the hills and mountains, sneaking among the dead leaves so as to look like a small rodent. Another name that suits him well is that of “foraboschi” (wood driller) or “foramacchie” (scrub driller), precisely for the ease with which he wanders among the branches and brambles.

Certainly curious is the fact that almost everywhere it is called the King of birds and, with this name, Antonio Valli already called it in the 1600s, in one of the first texts of Italian ornithology. Such a high-sounding name undoubtedly derives from one of the most ancient Anglo-Saxon legends, in which it is dreamed that the wren managed to be elected king of all birds with a trick: whoever managed to fly higher would have been proclaimed king. The eagle hovered over everyone sure of being crowned, but a wren was hidden between the feathers of its tail, and coming out at the right moment, it passed it by a few centimeters, singing its triumphal song from up there.

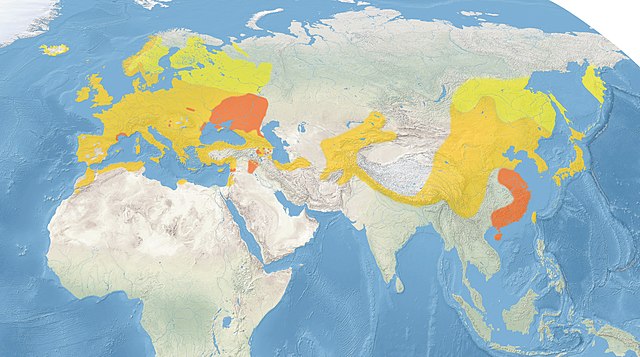

Its distribution range is huge and unusual, occupying much of the Arctic hemisphere from California to Asia. Indeed, it seems that the primitive origin of the family is North America, from where the wren would later come to us, constituting one of the infrequent species with the holarctic distribution.

Una dozzina sono le forme sotto specifiche descritte, quelle che una volta eran dette razze geografiche, con cui si adatta a situazioni climatiche e di habitat tanto differenti. Del tutto complessa è anche la situazione dei movimenti, in quanto esistono popolazioni migratrici ed altre stanziali. Le prime durante le migrazioni si mescolano alle seconde durante lo svernamento, con fluttuazioni popolazionistiche ancora non descritte compiutamente. I movimenti sono sia latitudinali (nord sud e viceversa) sia di quota, scendendo in pianura con il freddo da habitat in quota.

There are a dozen forms described under the described specifications: those that were once called geographic races, which adapt to very different climatic situations and habitats. The aspect of its movements is also highly complex, as there are migratory and also resident populations. The former during migrations mix with the latter during wintering, with population fluctuations not yet fully described. The movements are both latitudinal (north-south and vice versa) and altitudinal, descending to the plain with the cold from high altitude habitat.

Yellow: summer visitor. Dark yellow: sedentary. Orange: wintering.

The sedentary individuals are linked to their territory throughout the year, maintaining a continuous singing activity and not only during the mating period, as happens for many other species of passerines. Its singing activity has both the meaning of keeping rival males away from the territory and being a central element of the courtship with which he ensnares several females at the same time; it is in fact a polygynous species. The possibility of dividing between several females seems to be linked in the first instance to the structural complexity of the habitat visited: the greater the density of the vegetation and its tangle, the higher the degree of polygamy. Availability of food and places to make its various nests are equally crucial. Additional factors that led to polygamy are the low participation of the male in the breeding of the young; the fact that it is only the female who hatches; the innate aptitude to build more nests in any case; the event of feeding offspring of other species or conspecifics by both the male and the female; a very loose couple bond.

The ultimate goal of a polygynous reproductive strategy lies in the male’s ability to inseminate more females, thus providing him with the possibility of carrying his genes more easily in subsequent generations. Furthermore, there is no doubt that the encounter with more females leads to greater genetic diversity … a fact which, as they say, certainly does not hurt in terms of evolution and stability of populations.

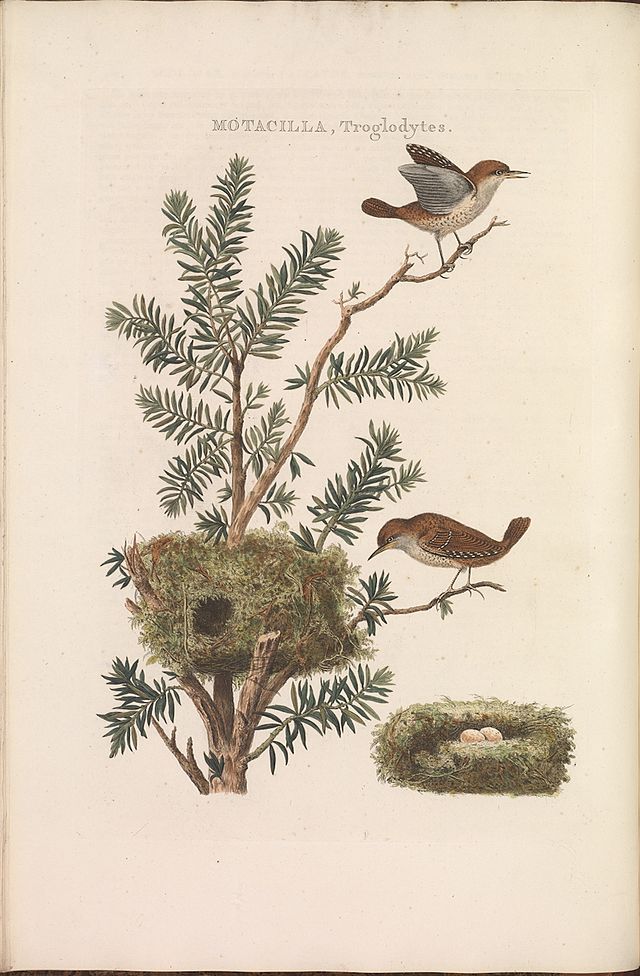

Generations of ornithologists have undertaken to describe the abilities of the male wren in building the nest, the female being nothing more than a finisher, giving her help only to complete the internal padding. Among these, Bacchi della Lega, an ornithologist from Romagna of the nineteenth century, says: “Power of a god who brings together in this little creature the skill of a weaver, the genius of an architect, the heart of a head of a family, the wisdom of a sage!”

In fact, he places it in the most varied places, natural and otherwise, but always well sheltered: a hole in the ground, a split in a tree, the interior of a dilapidated house, a woodcutter’s hut, nests abandoned by other species such as the swallow and, why not, in the pocket of an old coat hanging in a garage or in the engine compartment of an abandoned car. The shape is globular, with multiple layers, which, while on the outside look like a mass of dry leaves, reveal on the inside the careful interweaving of fine plant material, moss, baby food, and cobwebs, as soft support for the eggs to come. On the side, he leaves a round entrance hole into which a finger can hardly penetrate: a safe shelter from predators and bad weather. This is a crucial factor for a species of tiny body mass, easy to lose heat, and therefore of high adaptive value. He will build several nests, scattered throughout his territory with various functions, both to accommodate the different females of his harem, if in the polygynous phase, and as temporary shelters: if the females are hatching, he certainly does not want to stay out in the open at night.

To remember (for the writer) are the episodes experienced in Sardinia (where a subspecies different from that of the continent lives) when a wren got entangled in the nets we tended to study spring migration on the island. Lively and enterprising, they couldn’t bear to be trapped, reacting fiercely, eventually forming an inextricable ball with the fabric of the net bag. This made the recovery operation similar to the untying of the famous Gordian knot. Moreover, in dozens and dozens of cases, it was always the lowest net bag to catch them, given their ability to sneak in the undergrowth. Kneeling on the ground, trembling softly so as not to harm them: we lived nightmare moments, especially if what we were doing happened on the last evening lap before the nets closed. The danger was then that a bat would get entangled in the nets, given the impending darkness. In case… headlight, even more patience, and above all goodbye dinner!

Credits

Author: N. Emilio Baldaccini. Former Professor of Ethology and Conservation of Zoocenotic resources at the University of Pisa. Author of over 300 scientific papers in national and international journals. He is active in the field of science education, and co-author of academic textbooks of Ethology, General and Systematic Zoology, and Comparative Anatomy.

Translation by Maria Antonietta Sessa